Heretic: The Dilemma of Faith, Fear, and the Battle of Belief

In an era where discussions on religion, faith, and skepticism are often reduced to social media soundbites, Heretic arrives as a film that refuses to offer easy answers. Instead, it forces the audience into an uncomfortable space where belief is tested, doubt is weaponized, and the thin line between conviction and manipulation is dissected. But unlike the usual social media discourse, where opinions are flung with reckless abandon, this film plays out its arguments with meticulous craft, laying down its pieces like a well-calculated chess match.

Heretic does not ask the audience to choose sides—it simply presents a battle of ideologies and allows the viewer to wrestle with the implications. The premise is deceptively simple: two young Mormon missionaries, Sister Barnes (Sophie Thatcher) and Sister Paxton (Chloe East), knock on the wrong door. What follows is a night of psychological torment at the hands of Mr. Reed (Hugh Grant), a man who seems to have prepared his entire life for this very moment—a chance to systematically dismantle their faith using reason, history, and a chillingly calm demeanor.

Much like a well-structured stage play, Heretic confines most of its action to a single location, a choice that heightens the claustrophobia and intensity of the film. Every hallway, every dimly lit corner, feels like a trap waiting to spring. The setting is not just a house—it is an intellectual battleground where every exchange carries the weight of existential stakes. With each passing moment, it becomes clear that this is no mere thriller; this is a cinematic debate, a test of ideological endurance.

Hugh Grant’s performance as Mr. Reed is a revelation. Known primarily for his charming, affable roles, Grant turns those same qualities into something unnerving—a man who speaks with the patience of a professor but with the precision of a predator. It is not just what he says but how he says it, each line delivered with the careful calculation of someone who has rehearsed his points a thousand times over. His ability to weaponize doubt is chilling, and his methodical approach to psychological manipulation is one of the film’s strongest elements.

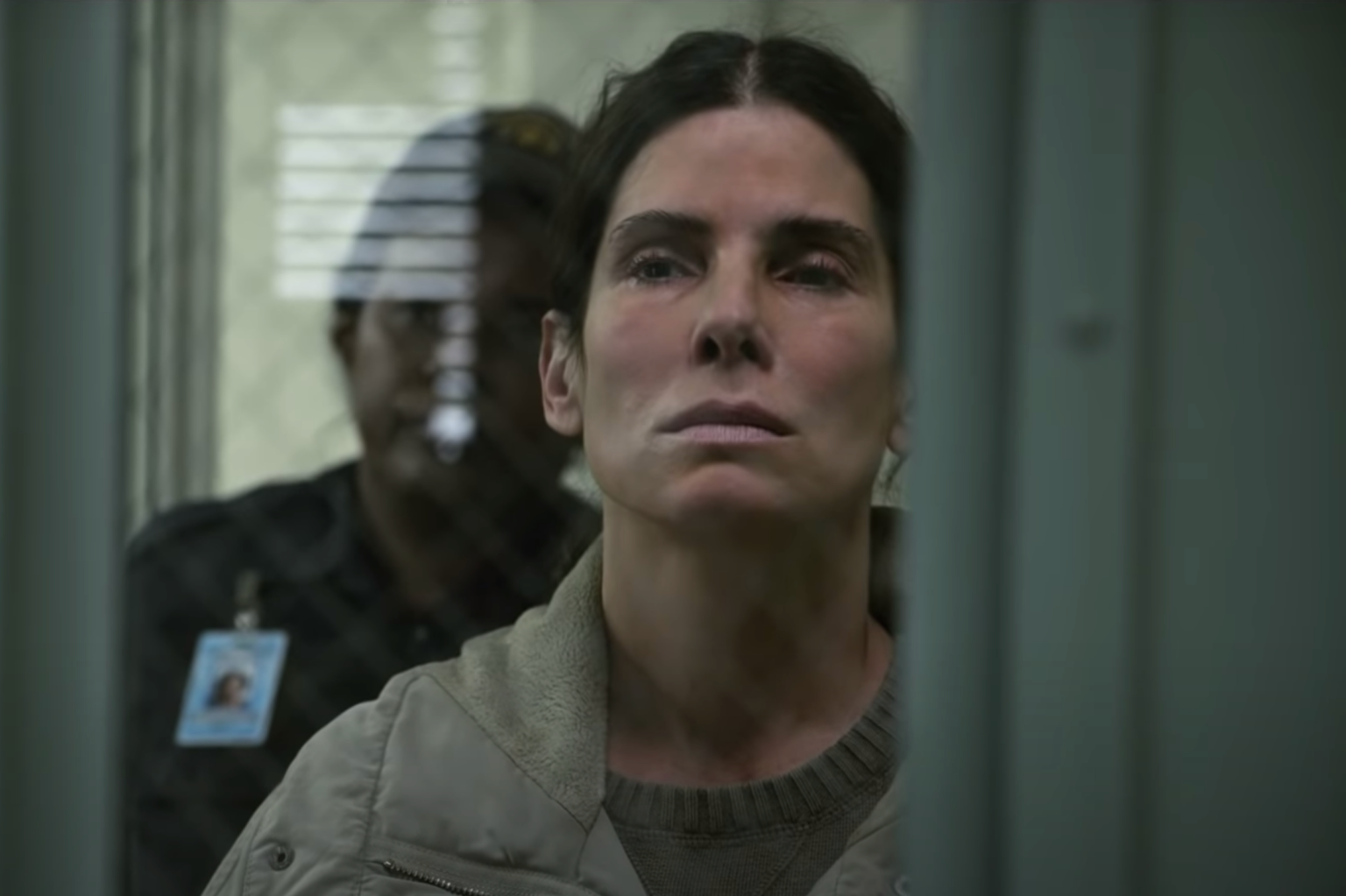

On the other side of the battle are Sophie Thatcher and Chloe East, who embody two different responses to crisis: defiance and self-doubt. Their performances give Heretic its emotional weight, ensuring that the film does not simply become a cold philosophical exercise but a deeply personal struggle for identity and belief.

At its core, Heretic is less about providing answers and more about posing unanswerable questions. It does not ask whether faith is real or if atheism holds the ultimate truth. Instead, it explores the idea that certainty—whether in belief or disbelief—can be a dangerous thing. Mr. Reed presents his arguments with an air of absolute confidence, but the film subtly asks whether his certainty is any different from the missionaries’ unwavering faith.

The movie carefully avoids the pitfall of making Mr. Reed an outright villain in the traditional sense. His arguments are not without merit, and for a large part of the film, it is hard to dismiss his points outright. But the way he delivers them—coercion disguised as enlightenment—forces the audience to question not just his beliefs, but his motivations. The true horror of Heretic is not in jump scares or supernatural forces but in the realization that certainty, when wielded as a weapon, can be just as dangerous as ignorance.

Critics will see Heretic through different lenses, as they always do. Some will interpret it as an attack on faith, while others will see it as an exploration of resilience in the face of doubt. The film does not exist to satisfy either camp, nor does it seek to convert anyone to a particular viewpoint. Instead, it thrives in ambiguity, presenting faith and skepticism not as opposites, but as two forces locked in an eternal dance.

At the end of it all, one thing remains clear—Heretic is not interested in easy conclusions. It leaves the audience in a state of reflection, ensuring that the discussion does not end when the credits roll. And perhaps that is its greatest achievement. Because in a world obsessed with drawing lines and picking sides, Heretic reminds us of an undeniable truth:

“You have your way, I have my way, but the one and only way … does not exist.” – Friedrich Nietzsche